Kiswahili spread as trade language thanks to Arab caravans during the 18th and

the 19th centuries. It reached the Democratic Republic of the Congo as far as

the river Congo and down to the south east. Later, with the extensive exploitation

of copper mines many people of diverse tribes from neighboring provinces and

countries such as Zambia, Rwanda, Burundi and Angola, poured into the

area. With the pouring of linguistically disparate labor forces,

the resresort to Kiswahili seemed the most practical and suitable solution.

As the mines prospered, so did the use of the consolidation of a new variety

of Kiswahili–E. Polomé talks about creolization–in cities such as Lubumbashi, Likasi

and Kolwezi as newly multiethnic space. In the most recent time.

The linguistic complexity of the Katanga province is a mere reflection of the

whole country where at least two hundred and fifty languages co-exit. French

was imposed as the official language and four languages among which Kiswahili,

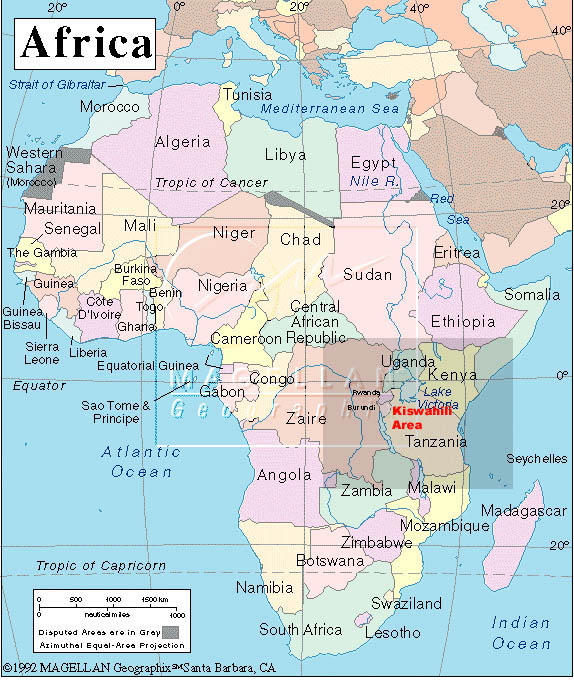

gained the status of linguae francae . The Kiswahili area comprises the

Oriental province, Maniema, South Kivu, North Kivu, Katanga, Western Kasai

and Easter Kasai. Till the Nineties, about half of the city populations in the Katanga

provinces were from or of Kasai stock, that is, mainly native speakers of L languages

such as Ciluba (L32 & L33). Their number has been diminished because of ethnic

cleansing under the authority of nativist politicians of the Mobutu-era.

It is estimated that about half a million people were thus displaced

from Katanga to the Kasais. The Copperbelt Kiswahili was influenced a great

deal by other Bantu languages represented by respective native speakers.

Among the most important ones are Kiluba-Shankadi, Ciluba-Kasai, Kisanga,

Kibemba, Rund’, Kihemba.

Kiswahili spread as trade language thanks to Arab caravans during the 18th and

the 19th centuries. It reached the Democratic Republic of the Congo as far as

the river Congo and down to the south east. Later, with the extensive exploitation

of copper mines many people of diverse tribes from neighboring provinces and

countries such as Zambia, Rwanda, Burundi and Angola, poured into the

area. With the pouring of linguistically disparate labor forces,

the resresort to Kiswahili seemed the most practical and suitable solution.

As the mines prospered, so did the use of the consolidation of a new variety

of Kiswahili–E. Polomé talks about creolization–in cities such as Lubumbashi, Likasi

and Kolwezi as newly multiethnic space. In the most recent time.

The linguistic complexity of the Katanga province is a mere reflection of the

whole country where at least two hundred and fifty languages co-exit. French

was imposed as the official language and four languages among which Kiswahili,

gained the status of linguae francae . The Kiswahili area comprises the

Oriental province, Maniema, South Kivu, North Kivu, Katanga, Western Kasai

and Easter Kasai. Till the Nineties, about half of the city populations in the Katanga

provinces were from or of Kasai stock, that is, mainly native speakers of L languages

such as Ciluba (L32 & L33). Their number has been diminished because of ethnic

cleansing under the authority of nativist politicians of the Mobutu-era.

It is estimated that about half a million people were thus displaced

from Katanga to the Kasais. The Copperbelt Kiswahili was influenced a great

deal by other Bantu languages represented by respective native speakers.

Among the most important ones are Kiluba-Shankadi, Ciluba-Kasai, Kisanga,

Kibemba, Rund’, Kihemba.

There is a range of terms used to designate this Kiswahili variant. Some refer to it as Kingwana, others as Katanga (Shaba) Kiswahili, others as Lubumbashi Kiswahili . Many other linguists–including me–prefer the term Copperbelt Kiswahili for two main reasons: